27 February 2011

26 February 2011

20 February 2011

19 February 2011

never forget flight

Thaddeus, Bianca and Selah painted balloons everywhere they could. They pulled up floorboards and painted rows of balloons onto the dusty oak. Bianca drew tiny balloons on the bottoms of teacups. Behind the bathroom mirror, under the kitchen table and on the insides of cabinet doors, balloons appeared. And then Selah painted an intricate intertwining of kites on Bianca's hands and wrists, the tails extending up her forearms and around her shoulders.

How long will February last, Bianca asked, stretching her hands out to her mother, who was blowing on her arms.

I really have no idea, said Thaddeus, who watched the snow fall outside the kitchen window.

In the distance the snow formed into mountains on top of mountains.

Finished, her mother said. You will have to wear long sleeves from now on. But you'll never forget flight. You can wear beautiful dresses--that's what you can wear.

Bianca studied her arms. The kites were yellow with black tails. The color melted into her skin. A breeze blew over the fresh ink and through her hair.

Light Boxes, Shane Jones

Light Boxes, Shane Jones

16 February 2011

15 February 2011

13 February 2011

Wallace Stevens on a February Night

The House Was Quiet and the World Was Calm

The reader became the book; and summer night

Was like the conscious being of the book.

The house was quiet and the world was calm.

The words were spoken as if there was no book,

Except that the reader leaned above the page,

Wanted to lean, wanted much to be

The scholar to whom his book is true, to whom

The summer night is like a perfection of thought.

The house was quiet because it had to be.

The quiet was part of the meaning, part of the mind:

The access of perfection to the page.

And the world was calm. The truth in a calm world,

In which there is no other meaning, itself

Is calm, itself is summer and night, itself

Is the reader leaning late and reading there.

---

The Motive for Metaphor

You like it under the trees in autumn,

Because everything is half dead.

The wind moves like a cripple among the leaves

And repeats words without meaning.

In the same way, you were happy in spring,

With the half colors of quarter-things,

The slightly brighter sky, the melting clouds,

The single bird, the obscure moon--

The obscure moon lighting an obscure world

Of things that would never be quite expressed,

Where you yourself were not quite yourself,

And did not want nor have to be,

Desiring the exhilarations of changes:

The motive for metaphor, shrinking from

The weight of primary noon,

The A B C of being,

The ruddy temper, the hammer

Of red and blue, the hard sound--

Steel against intimation--the sharp flash,

The vital, arrogant, fatal, dominant X.----

The Poem That Took the Place of a Mountain

There it was, word for word,

The poem that took the place of a mountain.

He breathed its oxygen,

Even when the book lay turned in the dust of his table.

It reminded him how he had needed

A place to go to in his own direction,

How he had recomposed the pines,

Shifted the rocks and picked his way among clouds,

For the outlook that would be right,

Where he would be complete in an unexplained completion:

The exact rock where his inexactness

Would discover, at last, the view toward which they had edged,

Where he could lie and, gazing down at the sea,

Recognize his unique and solitary home.11 February 2011

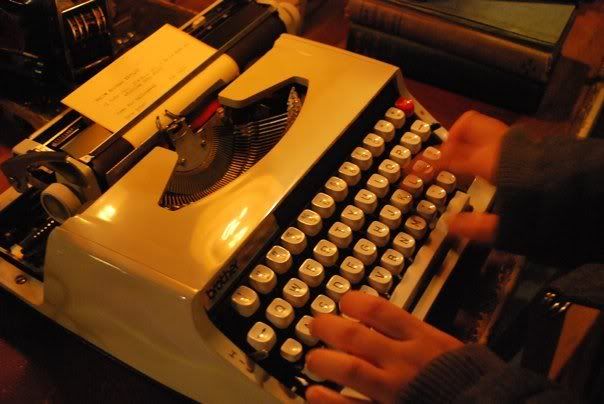

Where Is Poetry Going?

by Charles Simic

This is a question poets get asked often. The quick answer is nowhere. This can’t be right, you are thinking. You’ve read plenty of poems about poets walking in the woods, rolling in the hay and even taking a sightseeing trip through hell. True enough. Nevertheless, poets, even when they are fighting in a war, rarely take off their slippers. Doesn’t Homer’s blindness prove my thesis? I bet every one of those eyewitness accounts of Greeks and Trojan slaughtering each other, and the wonderful adventures Odysseus had cruising the Mediterranean, were dreamed up by Homer while waiting for his wife to serve lunch.

Sure, many poets would deny this. Here in the United States, we speak with reverence of authentic experience. We write poems about our daddies taking us fishing and breaking our hearts by making us throw the little fish back into the river. We even tell the reader the kind of car we were driving, the year and the model, to give the impression that it’s all true. It’s because we think of ourselves as journalists of a kind. Like them, we’ll go anywhere for a story. Don’t believe a word of it. As any poet can tell you, one often sees better with eyes closed than with eyes wide open.

Am I claiming, you are probably asking yourself, that most things that happen in poems are not true at all? Far from it. Of course they are true. It’s just that poets have to do a lot of time-wasting to get to the truth. Take my case. One day, out of the blue, the memory of my long dead grandfather comes to me. My eyes grow moist seeing him in the last year of his life limping around the yard on his wooden leg throwing some corn to the chickens. I recall the mutt he had then, and I put him in a poem. There’s even a rusty old truck in the yard. The sun is setting while my grandmother is fussing over the stove and my grandfather is sitting at the kitchen table thinking about the vagaries of his life, the stupidity of the coach of the local soccer team and the smell of bean soup on the stove. I like what I got down on paper so far and fall asleep that night convinced I have a poem in the making.

The next day I’m not so sure. The sunset is too poetic, the depiction of my grandparents is too sentimental, and so much of it has to go. Weeks later—since I can’t stop tinkering with the poem—I arrive at the conclusion that the old dog lying in the yard surrounded by the pecking chickens and the rooster is what I like best. The sun is high in the sky, a cherry tree is in flower, and the grandfather is out of the poem entirely. Typically, I have no idea if there will ever be a poem. Only God knows, and I try not to butt into his business. I strain my ears and stare at the blank page until a word or an image comes to me. Nothing genuine in a poem, or so I have learned the hard way, can be willed. That makes writing poetry an uncertain and often exasperating undertaking. In the meantime, there’s nothing to do but wait. Emily Dickinson looked out her window at the church across the street while waiting; I look out of my window at the early darkness coming over the fields of deep snow.

“Poetry dwells in a perpetual utopia of its own,” William Hazlitt wrote. One hopes that a poem will eventually arise out of all that hemming and hawing, then go out into the world and convince a complete stranger that what it describes truly happened. If one is fortunate, it may even get into bed with them or be taken on a vacation to a tropical island. A poem is like a girl at a party who gets to kiss everybody. No, a poem is a secret shared by people who have never met each other. Compared to the other arts, poets spend most of their time scratching their heads in the dark. That’s why the travel they prefer is going to the kitchen to see if there is any baked ham and cold beer left in the fridge.

10 February 2011

09 February 2011

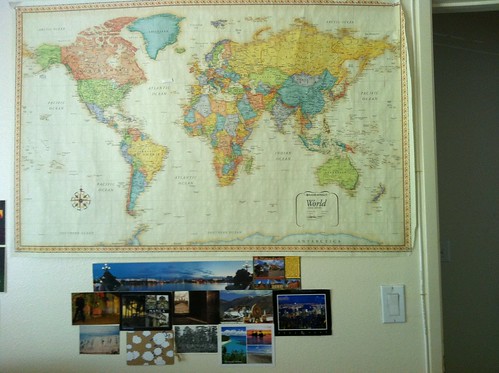

dear, send me postcards

tell me stories

hamburg, wattenbek

berlin, manila, angkor wat, lhasa, hong kong

every place, taipei, edinburgh, boracay

06 February 2011

04 February 2011

Ólafur Arnalds at Great American Music Hall, San Francisco

last night, óli arnalds played a stunning set in san francisco.

in his own words, "it was rad."

the great american music hall was the perfect venue

to experience his music--

it was intimate

but roomy enough

for some people to lie on the floor

midway through his set.

listen:

Labels:

concerts,

music,

ólafur arnalds,

san francisco

03 February 2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)